Equivocal…Equivalence?

By Andrea Musumeci

General theory of translation has notoriously suffered the blow inflicted by the inability of scholars to find a homogeneous academic dialect. James S. Holmes feared that this lack of cooperation could confine translators to a status of “glorified typist” (1994: 103) and nothing more than that.

General theory of translation has notoriously suffered the blow inflicted by the inability of scholars to find a homogeneous academic dialect. James S. Holmes feared that this lack of cooperation could confine translators to a status of “glorified typist” (1994: 103) and nothing more than that.

How did this status quo originate? Could the ‘equivalence precept/culture’ in Translation Studies (hereinafter TS) have played its role in this situation? Has equivalence been a major obstacle for translators, created by translators themselves? In addition, what could be done to change it?

Recent research on these matters has led to the implementation of the term/concept optimal approximation. Elements and evidence, drawn mainly from Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky, 1993, hereinafter OT), a theory of Linguistics, and from Translation Theories.

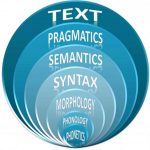

OT was developed by Alan Prince and Paul Smolensky (1993, 2002), in linguistics, precisely phonology, in 1993. It posits that the surface elements of language, i.e. natural language, are the result of an interaction process amongst competing constraints. The basic assumption within OT is that all languages share the same constraints (universal grammar), and it would be the hierarchical ranking of these to be differentiated in language use, upon well-formedness conditions. For exhaustive descriptions of OT, see Rene Kager (1999), John McCarty (2001), and Diana Arcangeli and D. Terence Langendoen (1997).

OT has enjoyed an evolution and a widening of its scope to an array of different disciplines, from bible exegeses (Parker, 2004) to computational linguistics (Quan, Federico and Cettolo, 2005), to cultural studies (Andreas Giannakoulopoulos, 2001). Particularly within linguistics, by means of its flexibility of its application, OT has exerted a function of mediator and unifier among theories, which were seen as diverging and opposing. The same role and function could therefore be ‘stretched’ and applied within TS whereby OT would function as an umbrella under which theories of translation would not be seen as contrasting per se but as cooperating, competing, and combinable. It would function as an alternative way to account for the phenomena related to translation in all their instances, independently from the genetic makeup of the languages at work. It would not only give a more enhanced sense of control to the translator over his or her work, but also a more homogenous approach. If translators could apply such approach as a category, may flatten the hills raised during centuries of different theorization in different parts of the world, and create a levelled ground for discussion for a more harmonic progress of the whole field of study.

The application of OT to translation would sustain the idea that equivalence should not be the underlying motor of the translator’s search, but rather that its motive and scope could be defined in terms of optimal approximation. The latter concept, as sustained by Alì Darwish (2008), and as demonstrated by Richard Mansell (2004) and Christine Calfuglou (2010), is found to be more ‘politically and ethically correct’ when confronting ourselves with languages.

OT displays three core dimensions: Input, Eval. (uator), and Output, which cooperate and operate through filters and ranked constraints. “One of the main characteristics of an optimization approach to grammar is the assumption that linguistic rules are not hard and inviolable, but rather soft and violable” (Hendriks, De Hoop and Krämer, 2010:3). In other words, the previous Chomskian fashion of inviolable principle and parameters (Chomsky, N. and Lasnik, H. 1993), which had struggled in dealing both with irregularities and with natural patterns in language were seen by Prince and Smolensky as a highly valuable, but limited approach. The two theorists supplemented the deep grasp of the cognitive mechanism of language acquisition and development with the notion of violable constraints as opposed to inviolable principles to come to terms with how universal grammar becomes natural language.

In OT, possible output candidates from a given input, which compete for expression, are generated by the mechanism of GEN, which stands for ‘Generator’. These candidates are then evaluated based on the set of ranked constraints, called EVAL (for ‘Evaluator’).

In the case of translation, the analogy would be the following: a source text (hereinafter ST) or an ST element will function as the input. The source language (hereinafter SL) and target language’s (hereinafter TL) systemic requirements will function as generator of all the possible outcomes for the translation of that input. The translator, therefore, will not only have an active role in the formulation of the candidates to consider, but also in the choice of the final output, which may be in accordance with what is indicated by EVAL (represented through OT evaluative tables) as the optimal candidate, or in accordance with external factors. Darwish (2008: 210) delineates the existence of internal and external constraints to translating. The translation brief, ideology, and cultural constraints may be examples of the latter type, while linguistic constraints are the internal ones.

The acquisition of this new frame of mind may reveal itself useful in taking distance from euro-centrism, and in embracing a more collaborative international academic and professional environment, insofar as it could be exploited independently from the origin of the particular languages at work. As claimed by Maria Tymoczko, the abandoning of euro-centrism would entail the re-adaptation of the mere definition of translation, “for if the definition of translation and other objects of study are bounded by Western experience or centred on Western prototypes, it will be hard for the field to go beyond those very delimiters” (Tymoczko, 2005: 11, italics in the original). The different traditions and the wide variety of contributions that they could bring to the field as a whole, are somehow -‘lost in translation’- because of lack of a ‘lingua franca’ among translators themselves.

It is crucial not to forget the role of the translator in all this. The subjectivity of the translator plays a fundamental role in the process, which is conducted by a human being, with his own linguistic and cultural competence.

In the light of this, the constraints in action would have to operate in a similar fashion: they must be universal, in terms of an objectively undeniable truth, yet, when applied to translating, they must take into account the human agent and the specific settings of a particular piece of work. Different surgeons perform the same operation differently; the subjectivity in their field is their particular touch or experience. The same applies to translation. Therefore, with respect to the application of new approaches, the issue of scientific grounding is not to be underestimated because of the subjectivity, creativity element involved.

As a final point deserving consideration, it has to be said that TS has always drawn experimental methods from other disciplines, most notably linguistics, comparative literature, and more recently, cultural studies. This has contributed to the fact that TS still struggles to be considered as an independent science, or area of study. Gideon Toury posits that the advantage of experimentation (with tools taken from other disciplines)“ lies precisely in its potential for shedding light on the interdependencies of all factors which [may] act as constraints on translation and on the effects of these interdependencies on the process, its products… and increasing their predictive capacity” (Toury 1995: 221-222, square brackets in the original).

It is here that the application of OT to translation may be both conservative and transgressive: the use of linguistic theory does not signify at all that TS is subordinate to linguistics. It is instead a confirmation of the independent status of TS as a discipline which can now afford to ‘borrow’ methodologies and devices from other disciplines and model them to its needs, not having the ‘superimposed’ status of being ranked a secondary science, which could only function if annexed to a ‘superior’, or more established one.

This article was an attempt to outline the notion of optimal approximation in terms of similarities and differences from the more traditionally equivalence-related doctrines in TS. It is hoped that the conceptual and ethical stance behind the idea, the advantages and disadvantages with respect to its application to TS, may lead to the creation new areas for debate in the field. Furthermore, the research conducted has led to exciting perspectives on future studies.

References

Archangeli, D. and Langendoen, D. (1997). Optimality Theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Calfoglou, Christine. (2010). “An optimality approach to the translation of poetry” in Fawcett, A., Guadarrama, K. and Parker, R. H. (2010). Translation. London: Continuum.

Darwish, Ali. (2008). Optimality in translation. Melbourne: Writescope.

Gawron, J. (2009). “Optimality theory reading list”. Retrievable at http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~gawron/optimality/reading_list.pdf last accessed on the 25th March 2014.

Gentzler, E. (1993). Contemporary translation theories. London: Routledge

Giannakoulopoulos, A. (2001). Frog leaps and human noises. An OT approach to cultural change. Thesis (MA). Institute for Logic, Language and Computation. Retrievable at http://dare.uva.nl/document/443329 last accessed on the 31st July 2014.

Hendriks, P., De Hoop, H. and Krämer, I. (2010). Conflicts in interpretation. London: Equinox.

Holmes, J. S. (1994). Translated! Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Kager, R. (1999). Optimality theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mansell, Richard. (2004). ‘‘Optimality Theory applied to the analysis of verse translation‘‘. University of Sheffield / Universitat de les Illes Balears. Retrievable at http://roa.rutgers.edu/files/665-0504/665-MANSELL-0-0.PDF Last accessed on the 7th September 2014.

McCarthy, J. (2008). A thematic guide to Optimality Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCarthy, J. (2008). Doing Optimality Theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Newmark, P. (1981). Approaches to translation. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Nord, C. (1997). Translating as a purposeful activity. Manchester: St. Jerome.

Parker, M. (2004). Optimality Theory and ethical decision making 1. Citeseer. Retrievable at http://www.sil.org/resources/archives/40079 last accessed on the 15th August 2014.

Prince, A. (2002). “Arguing optimality”. Papers in optimality theory II, 26, pp.269–304. Retrievable at http://roa.rutgers.edu/files/562-1102/562-1102-PRINCE-0-0.PDF last accessed on the 20th August 2014.

Prince, A. and Smolensky, P. (2004). Optimality theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Prince, A. and Smolensky, P. (2002). Optimality Theory: constraint interaction in generative grammar. Retrievable at http://roa.rutgers.edu/files/537-0802/537-0802-PRINCE-0-0.PDF Last accessed on the 7th September 2014.

Quan, V., Federico, M. and Cettolo, M. (2005). “Integrated n-best re-ranking for spoken language translation”. Proc. of the 9th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology, Interspeech’05.

Reiss, K. and Rhodes, E. (2000). Translation criticism, the potentials and limitations. Manchester: St. Jerome.

Reiss, K., Vermeer, H., Nord, C. and Dudenhöfer, M. (2013). Towards a general theory of translational action. London: Routledge.

Toury, G. (1995). Descriptive translation studies– and beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Tymoczko, M. 2010. Translation, resistance, activism. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

—-. (2005). “Trajectories of research in translation studies”. Meta: Translators’ Journal, 50(4), pp.1082–1097. Available at http://www.erudit.org/revue/meta/2005/v50/n4/012062ar.html last accessed on the18th August 2014.

For an overview of our translation expertise, visit our translation service page.

Category: Translation Tools