The glow of the big screen illuminates the Parisian movie theater’s engrossed occupants. This is the latest American blockbuster and while the French audience gapes at the big-shot actress in the opening scene, they also tune in to a very familiar voice. The voiceover sounds exactly like the middle aged woman from last week’s showing, briefly taking the audience out of the verisimilitude. It is a mystery who the French male and female voiceover professionals are, working from behind the screen, but their voices, broadcast to millions of spectators, aren’t varied enough to serve all of Hollywood’s acting crew. Yet here is a business where machines could never replace humans whose voices must express drama and excitement in the millions of new shows and movies being spewing out. This introduces a much broader topic, machine interpretation. Machine Translation (MT) is a hot topic in the 21st century language world, despite its rudimentary vocabulary and poor handling of grammar and regionalisms. If the text is barely useable, what about simultaneous voiceovers between foreigners in a futuristic conversation? What about machine interpretation of telephone conversations, theater productions, speeches, and conferences?

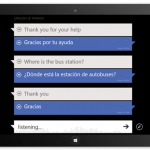

This concept has been dubbed Speech-to-Speech translation and it presages that the familiar (or annoying) voiceover or customer service voices that are heard everywhere will make their way into headsets and speakers. Or for those iPhone users who have met Siri… one of her relatives may one day eliminate language barriers and replace the thrill of speaking to a foreign person, hearing a foreign accent, struggling with a language, or discovering a culture. If Speech-to-Speech actually worked! The acoustic model is the speech recognition tool which picks up audio waves to convert them to text. The machines work wonders when presented with a slow even speech pattern but when the sports channel comes on or Italians tune in, speedy talking will invariably undermine their efficiency. The same goes for mumbling, slurring and background noise. Not to mention spoken vocabulary is a far cry from textual vocabulary because people add fillers, hesitations, colloquialisms and generally what researchers call OOV (Out of Vocabulary) words. Despite this, speech recognition has undergone constant innovation, notably by Microsoft. While Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) were the go-to-method in deciphering which phonemes were being spoken to reconstruct words, DNN (Deep Neural Networks) are the attraction of recent years. In fact, Microsoft Research has developed a version of this last method, which mimics human neurons in its way of processing phonemes, that uses senones instead. Senones are even shorter fragments of sound in the human voice which greatly improve accuracy. However, Microsoft’s 2010 version still recorded errors in one out every eight words. In a typical three minute telephone conversation, that’s equal to fifty wrong words!

Furthermore, the cost of accuracy is the information it requires. Senones outnumber phonemes by the thousands (and presumably more in phoneme rich African languages) and together with repertoires for different accents means machines will have to be well equipped. Especially when it comes time for the machine translation process which relies on statistical information. Either the Nano age and the storage of terabytes in small chips cannot come soon enough or information will have to be kept in the cloud, where it is prone to leakage. While private interpreting firms have confidentiality statements about information that is translated, the Japanese NTT DoCoMo cell phone company sends all information to a central database in its attempt to simultaneously translate phone calls. There are other dangers in dependence on machine translation but what about the robotic voice that emits the translation vocally? While Siri is excellent at voice recognition, its responses are very limited. The same is for eBooks that have to be specially recorded, while being the most obnoxious sounding bed time story you’ve ever heard. And finally there’s the potential for new gaffes. The embarrassment of a woman’s dialogue being simultaneously translated into a man’s voice, or the voices of several interlocutors being translated as if one person was speaking, or yet again, if a snarling foreigner was given a cheery tone by the machine voice. And think of the uproar caused by Google Glasses… what would people think if everyone travelled with headphones in their ears? Perhaps they are marketable to the French movie buffs that need an alternative to the same person doing all the voiceovers!

For an overview of our translation expertise, visit our audio and video translation page.