Archipelagos reserve interesting anthropological surprises. One such surprise is the existence of a distinct minority group living in Japan, a society known for its hegemony. They are called Ainu, number around 15,000 and occupy, for the most part, Hokkaido, a northern island whose luminous plains cut by volcanic mountains becomes a shadowed white wilderness when winter arrives. And while the Far Eastern nation’s beautiful landscapes submit to urbanity under newfound demographic pressure with low nativity rates and long life-spans, the Ainu people’s language, historically marginalized and on the brink of extinction, is being relieved of some pressure. Courses are appearing in universities and language centers to preserve this ethnic language that owes its improbable survival to the characteristic long life-spans. This is shown by a 1989 study revealing only 30 native speakers, all octogenarians. Meanwhile the total number of speakers can be estimated around 300, all in Hokkaido.

Ainu speakers had also lived in Tohuko, Sakhalin (Russia) and the Kuril Islands (Russia) in supposedly great numbers. The last speaker in Russia died in 1994 which is recent, given that the Soviets deported Ainu people in 1949. Obviously poverty, disease, stigmatization in Japan politics, and intermarriage took their toll as well. Earlier, the nineteenth century had overseen extensive bilingualism, and before 1800 the Ainu were monolingual in their native language, according to Kirsten Refsing, a Danish researcher. This may be due to a 1604 decision banning Japanese in the north when the region had its autonomy. As an educational policy, banning Japanese was short-lived, and from then on, the Ainu could not “hold back the tide which washe[d] over [their] language and hollow[ed] it out” in the words of late Ainu activist Shigeru Kayano. Only in 1991 did the Japanese government admit the existence of a minority group while five years earlier a speech by former Prime Minister Nakasone had included “Japan has no racial minorities”. Finally, a 1997 district court ruling returned rights and gave long awaited recognition to the Ainu community.

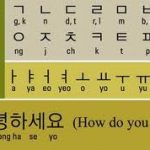

The language is not related to Japanese, in fact, its origins are still unknown. Various theories ascribe Ainu to different language groups such as Native American, Altaic, Austral-Asian, and Indo-European. The first theory is related to the theory of a land bridge between Kamchatka and Alaska while the last theory is largely speculative based on a few words from a 1905 dictionary. Nevertheless nothing can be excluded, and this 1905 dictionary written by the missionary John Batchelor is a step beyond an 1875 Russian attempt by Dobrotvosrky in Cyrillic script. Latin script is more adapted for non-gutteral languages like Ainu and has predominated, considering the language never had a writing system of its own. Instead, it relied on an oral tradition with famous hero sagas such as Kutune Shirka.

A few words in Ainu include “sapporo” (dry land) which is also the capital of Hokkaido, the absence of a term for “painting” yet two for “dog” (seta, reyep). More useful is how Batchelor introduces his dictionary, with the opener “Lyrangarapte” (How do you do?). The grammar is described as SOV (Subject Object Verb) with nouns that can be combined, and use of head-final, unlike English. Obviously the Proto-European origin claim may mean some relief for English-speaking learners, but in reality nobody is favored in this Ainu preservation challenge. The bravest, the heroic salvagers of a heritage which came within a thread of extinction are the researchers, journalists, and a new generation of university students enrolled in Waseda and Christian Univerisities in Tokyo and Chiba University where Ainu programs have been commenced for the first time in history. If all ethnic Ainu knew their language there would be no problem, but that is far from the case.

For an overview of our translation expertise, visit our medical and life science translation service page.