By Sarah-Claire Jordan

Japanglish, also known as “Engrish” and “Janglish”, is the term used for words used in Japanese that look and sound just like English words, but have different meanings. The Japanese term is wasei-eigo, which means “English made in Japan”. This is different from gairaigo, which means words from a foreign language used in Japanese, because those words retain their original meanings.

Japanglish, also known as “Engrish” and “Janglish”, is the term used for words used in Japanese that look and sound just like English words, but have different meanings. The Japanese term is wasei-eigo, which means “English made in Japan”. This is different from gairaigo, which means words from a foreign language used in Japanese, because those words retain their original meanings.

Wasei-eigo isn’t always something that translators have to worry about, as many of the terms make sense if you think about them. For example, a stroller is called a “bebii kaa”, which sounds very much like “baby car”, a term not used to refer to strollers but a logical one nonetheless. Translators still need to be aware of these terms and translate them accordingly into English, and also translate the English term into the appropriate and commonly-used Janglish term.

The real issues happen when you have terms in Janglish that have a very distant connection to the original English term, or don’t have a connection at all. An example would be “panku”, which can mean a flat tire, but can also mean a strain or overload. The original English it probably comes from is the word “puncture,” but the fact that it now means something unrelated to the original English means translators almost have to learn an extra language to translate texts that use Janglish accurately.

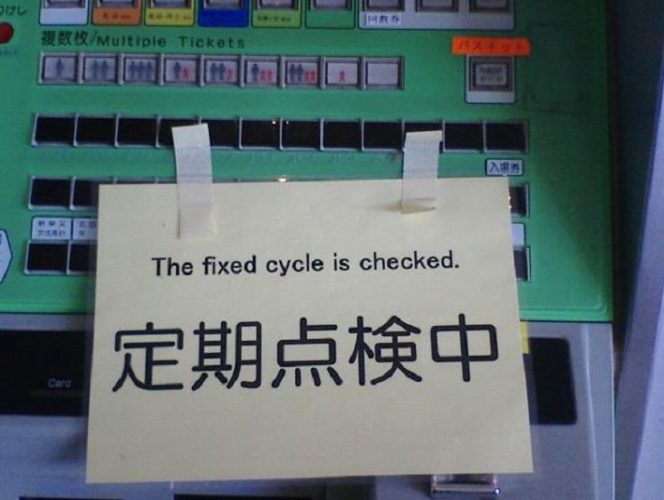

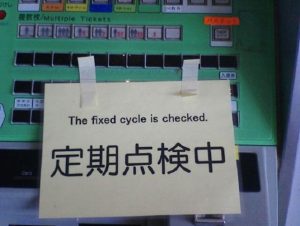

A huge issue among native Japanese speakers is the false notion that, if a word or phrase seems to be originally English, it has the same meaning as the English phrase. This leads to lots of confusion, where Japanese people might start saying Janglish words they know and use that mean absolutely nothing or something totally different in English. Some Janglish words don’t even come from English, yet are assumed to be as they fall into the Janglish category. This adds yet another layer of confusion that translators must peel back and examine while they work.

This whole issue touches upon another, which is the importance of localization, especially cultural localization. Doing research into the target market, like an English-speaking country by a Japanese company, would eliminate any mistakes in terms of equating Janglish terms with actual English. This is still an issue, however, as many of us can see when we look at the translations of products from Japan in stores and the media.

If we can get all Japanese-to-English translators on board and willing to keep their Janglish knowledge up-to-date, we can eliminate this issue soon. Of course, Janglish is a natural product of language evolution and exchange, and is not a problem except when it is confused for English. Translators should be properly trained in how to deal with any Janglish they encounter, and business owners should stay informed as well, taking English classes if necessary and relying on more knowledgeable colleagues and departments to deal with certain aspects of their business. With everyone working together to make sure there are no misunderstandings between the two cultures and languages, soon we won’t see any translation errors from Japanese to English.